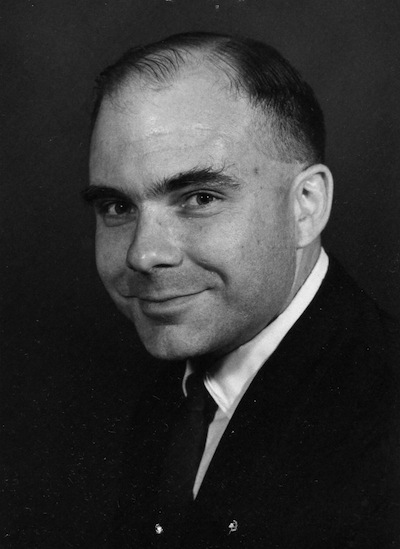

Biography: William Chancellor

In October 2007, three years after he retired from his academic career, the late William Chancellor, who was a professor of biological and agricultural engineering — was pleased to attend an event he helped bring about: the historical landmark plaque dedication for the world’s first self-propelled combine, invented by George Stockton Berry in 1886. The ceremony, which took place at the Tulare County Museum in Visalia, Calif., featured Berry’s family members, members of the Tulare County Historical Society, and members of the American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers.

Speaking at the ceremony, Chancellor explained that Berry had built his first six harvesters in 1886, which “firmly established the advantage of enhanced performance, reduced cost and better maneuverability for large, self-propelled machines.”

One month later, Chancellor was honored — as a longtime member of the UC Davis Quarter Century Club — for having achieved 50 years of service to the campus.

Chancellor’s interest in agriculture began in the 1940s, when — having grown up on a small Wisconsin dairy farm — the war effort reduced the availability of machines and fuel, amplifying the human burden of farming.

Chancellor’s interest in agriculture began in the 1940s, when — having grown up on a small Wisconsin dairy farm — the war effort reduced the availability of machines and fuel, amplifying the human burden of farming.

“I felt that reducing this burden might be an interesting field to get into,” he commented, during a 2005 interview.

He obtained joint undergraduate degrees in agriculture and engineering at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, followed by a master’s degree and doctorate at Cornell University, where he studied the problems of handling forage on dairy farms. He came to UC Davis in 1957 at the invitation of Roy Bainer, who wanted Chancellor involved with a statewide study of the problem of soil compaction caused by the use of heavy agricultural machinery.

Over the years, Chancellor became an expert on agriculture, energy and farming methods around the world. He recognized the inherent problem of modernized agriculture, which had become necessary to feed the world’s population, but which had abandoned the near-organic, generally sustainable methods of centuries past.

His career’s work was recognized in 2004, when he received the John Deere Gold Medal from the American Society of Agricultural Engineers, for his outstanding contributions as a researcher, educator, and extender of agricultural engineering knowledge. The following year, he was elected to the National Academy of Engineering, for contributions to the understanding of — and engineering innovations for — agricultural technology in the United States and developing countries.

“We need to find ways to maintain — and even increase — food production, while bringing adverse environmental impacts of materials and methods used as close to zero as possible,” he explained, during an interview following his NAE election, “all while conserving, and finding renewable substitutes for, nonrenewable resources like fossil fuels.”