A Computer Cursor that Moves Without Being Touched

By Sarah Colwell for Public Scholarship and Engagement.

Imagine turning on your computer and moving the cursor without ever touching it.

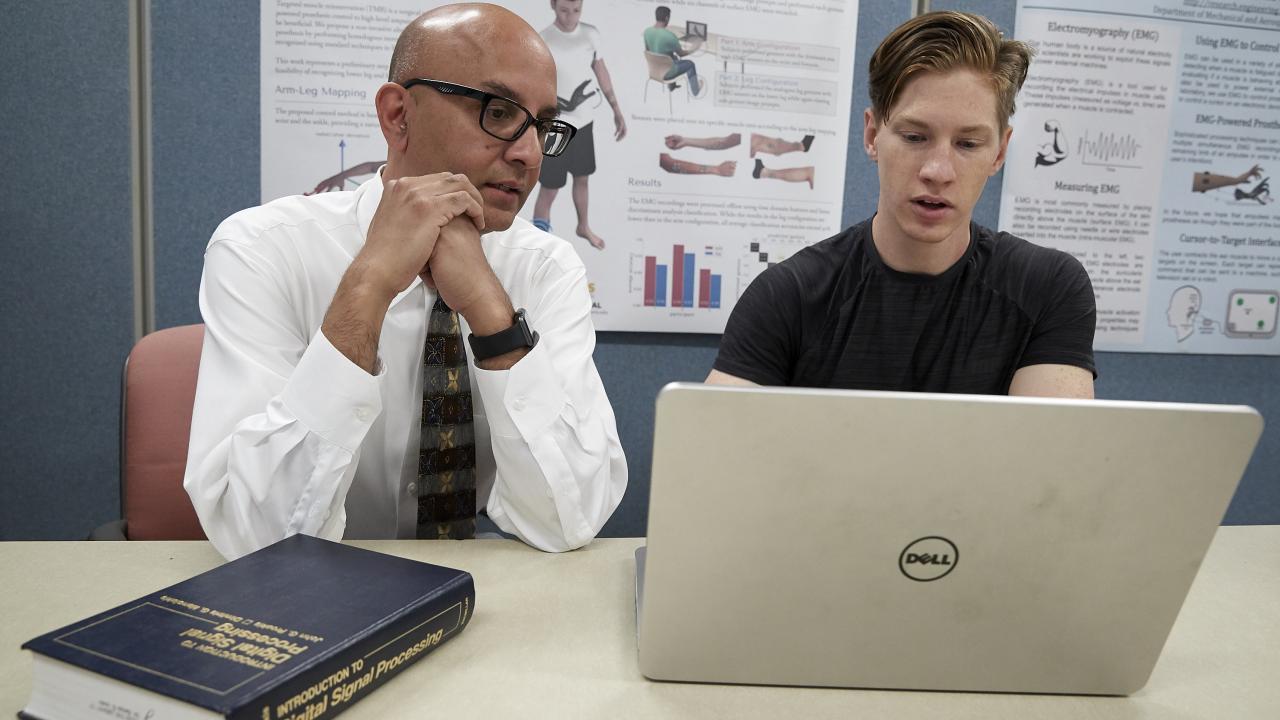

Sanjay Joshi, a professor in the Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering at UC Davis, and his lab are working with people in the medical, engineering, and disability communities to improve the capabilities of machines to assist people with physical limitations.

“Many of us use human-machine interfaces all day long. In our lab, we are trying to build interfaces so that paralyzed people can command devices, so that they can use cell phones, or turn on the TV or operate a computer.”

Space. The first frontier.

Joshi began his professional career at NASA, as an engineer that worked on control systems – to allow spacecraft to move in space and perform scientific functions. The job was a dream come true for Joshi, who had been fascinated with the space program since he was a child.

“I was one of those kids that got up in the morning when the space shuttle first launched and was glued to our 13-inch, black-and-white television at home,” he said. “I also remember there was an astronaut that visited my junior high school, who made a big impression on me. He handed out posters of the space shuttle and I’ve had that poster either in my room, house, or office ever since. I still have it in my office now.”

After several years at NASA, Joshi wanted to explore how techniques used in the space industry could be applied to other fields. He began working with people who had physical disabilities that made it difficult for them to use objects they needed for daily living. He and his team now work to make machines, that usually require human movement and touch for control, to be activated with natural electrical signals inside the human body. This means they must consider the intricate systems powering both machines and the human body. The complexity of these systems necessitates collaboration with colleagues from a variety of fields — engineers, physicians, scientists, and those living with limited mobility.

“We just have the most wonderful discussions and the most wonderful set of issues that come up when we are thinking about all of these fields together,” he added.

The ultimate control system

These partnerships with colleagues, coupled with his desire to build devices for people with severe mobility issues, inspired Joshi to advance his own understanding of the ultimate (and oldest) control system — the brain.

“If you are interested in control systems like me, there’s nothing that can beat the brain as a controller,” Joshi said with a laugh.

Joshi consulted with colleagues from UC Davis Health, the UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine, and others around the country to learn more about how the brain worked and how it stored and organized data and information. He then used his sabbatical to obtain a visiting professorship at Columbia University Medical School in the department of neurology.

“Now our lab has this network of researchers around the world that we are lucky enough to work with,” he said. “You get to work in these wonderful teams. There’s a lot of joy in working with different people who have many different kinds of knowledge.”

Beyond these academic partnerships, Joshi said perhaps the most important relationship his team has developed is with their partners in the disability community. They’ve learned a great deal from talking with and listening to people with disabilities and their families. An engineer may have an idea for a device they think would be useful, but after listening to the person with the disability, the researcher may discover it isn’t something people want or need.

“That’s the first thing that you learn,” Joshi said, “that they are partners with you, and only they know what’s best for them. We interact with our community partners with utmost appreciation and respect.”

“In fact, they don’t need our help in many ways. They really do appreciate the things we are doing to try and make things easier for them and others; but, honestly, they have learned to live happy, productive lives in the face of extreme challenges. So, it’s important for us as researchers and engineers to understand that, in many cases, they are helping us much more than we are helping them.”

From these partnerships, Joshi and his team are making advances in technology and medicine. After research focused on converting muscle signals into computer commands, his team is testing how human muscle electrical signals can be used to control assistive robots.

Muscling through Physical Challenges

Muscling through Physical Challenges

Aaron Negrete is a typical 10-year-old boy who is busy with schoolwork and interested in video games, but the challenges he faces are far different from those his schoolmates encounter. Born without arms or legs, Aaron must get creative to accomplish tasks. He uses his head to operate his wheelchair, his mouth to hold pens, and his nose to tap on a computer. But now, with the help of UC Davis robotics engineer Sanjay Joshi, Aaron is using his ears to potentially open up a new world of independence for other kids and adults with disabilities.