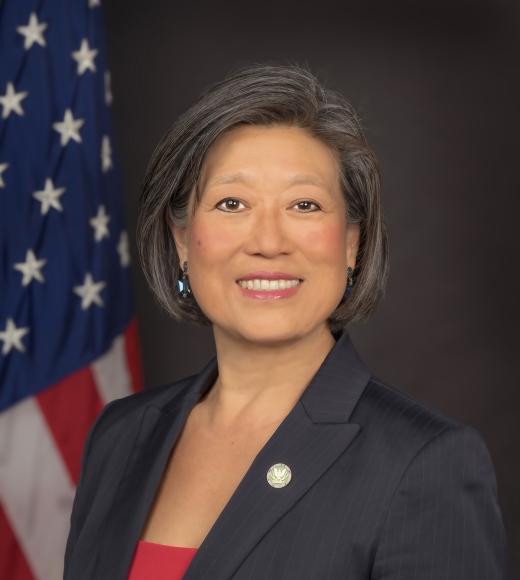

A Conversation with Federal Energy Regulatory Commissioner and Alum Judy Chang

Before Judy Chang was confirmed by the United States Senate as a Commissioner on the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission and the first Asian-American woman to serve on the agency, she influenced energy policy in Massachusetts and spent more than two decades researching renewable energy, electric power markets and energy resource deployment.

Before all of that, Commissioner Chang, who earned her bachelor's degree in electrical engineering and computer science at the University of California, Davis, was an undergraduate trying things out to see where the world would take her.

Chang talks about her new role in regulating energy infrastructure, thinking outside the box to find new solutions and how her love of electronic music brought her to UC Davis.

You joined the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, or FERC, as a Commissioner in July 2024. What does FERC do, and what are your responsibilities?

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission is a bipartisan federal agency that has five commissioners, appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate. The commission regulates the interstate transmission grid and wholesale electricity prices, including transmission rates and planning, as well as wholesale power markets. FERC has a legal requirement to make sure that the rates that consumers pay for electricity are just and reasonable.

What are your favorite aspects of the job?

My favorite part of the job is thinking through how our decisions might affect the way energy is provided and consumed across the U.S.

For example, if a particular entity comes before us and says, "Well, we want to make changes where we want to design a market for power in this particular way." This proposal might only be applicable to, say, New England or New York, but when we make a decision about New England or New York, we have to not only think about that jurisdiction, we also have to think, "Well, what happens if this similar entity or a different entity approaches us with similar proposals in a different part of the country? Would it still be applicable to a different kind of part of the country?"

There are lots of both legal and technical reasons why we do certain things a certain way. Some of it is history. Some of it is just legacy investment.

Our inclination as judges, effectively, is to just decide on the cases before us, which is very limiting. There are legal requirements of what we can decide or not decide, and there are strong legal precedents that we have to follow. But sometimes for us to think for the country and about where the country needs to go, we have to go beyond that constraint.

You earned a Bachelor of Science in electrical engineering and computer science at UC Davis before going on to earn your Master of Public Policy at Harvard Kennedy School. What inspired you to pursue engineering and why did you choose UC Davis?

Like any 18-year-old, I didn't really know what I wanted to study. I know this might sound silly, but I felt like I should start with the hardest major and then I could switch out of it if I needed to, but I could never switch into a harder major. It's just one of those things where you're in the program, and there was no reason to change, so I never changed.

There are side events that happened when I was at UC Davis that helped channel that. I had an opportunity to be a teacher's assistant at Davis [Senior] High School. It was a computer science class, and I think having a job that is parallel to what I was pursuing was helpful.

And the reason I chose UC Davis — this is probably pretty random. I went to one of these "Invite prospective students to come on campus" events, and I met someone who was really interested in electronic music, and I was too. Back then, what I really wanted to do with my electrical engineering was design synthesizers. This was in the '80s, so it was just the beginning of synthesizer music. Davis had an electronic music room, and I just thought that was the coolest thing back then. I met this guy who was studying electronic music, and he was like, "If you want to get a job on campus, you should talk to Professor so-and-so, and maybe he has research projects." That was the type of conversation that pulled me to Davis.

Why did you choose energy policy as a career path and what aspects of your UC Davis engineering education would you say best prepared you for that career?

After [graduating from] UC Davis, I started working for a telecom company, and that's where I realized that I'm very interested in infrastructure in general. So not necessarily energy, but infrastructure. Part of that is because I grew up in developing countries, both Taiwan and the Philippines before I came to California to finish high school. I knew what it was like to have dilapidated infrastructure, whether it's roads or bridges or ports or telecom and certainly energy infrastructure.

By the time I applied for graduate school, I knew that I wanted to pursue a degree that would help me work on infrastructure in general. I knew I wanted to be in this space where it's partially private and partially public, and it became clear to me that I'm interested in infrastructure development, and that went well with public policy programs.

Are there skills, knowledge or even advice you received from those undergraduate years that you apply to your position now?

All the skills I've learned are actually quite applicable to my current job. For example, I was an electrical engineer, and I'm in the power systems field. I regulate the power systems of this country, and to do that, I have to understand how the power system works, not only generically how it works, but also how the power flows, why it flows in a certain way and how the system operators operate their system.

On the computer science side, I've done a lot of modeling, computer programming and analytical work throughout my career. I personally don't do modeling now, but I know a lot about modeling and how other people model systems. These days, the energy system is modeled in so many different ways, and a lot of our decisions are based on model simulations of how systems work, either in the past or in the future. Our decisions are hinged on those things because we don't exactly know how our futures will look, so we use simulations of the future to help us make decisions.

Was there a professor or staff member that greatly impacted your education or career path? What was it that was so impactful?

Distinguished Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering André Knoesen taught electromagnetics when I was there, and it was probably one of the hardest courses I have ever taken. I remember really struggling with it and really trying to understand the concept. I tried to really do a good job, and I was really happy when I did well in that class.

Three years later, I was living on the East Coast, and I was getting ready to apply to graduate school, but I wasn't sure yet what I would pursue. I flew back to California just to meet with Professor Knoesen, because I wanted to get his thoughts and advice. He was just so nice to me, and he wrote me a recommendation letter when I applied to graduate school, which helped me get into Harvard. I've always been very grateful for his support, not only when I was in his class, but also afterward — how he received me, as like a student of the past, very warmly and talked about the classes and what I want to do. I think that's hard to do at large schools because it's not like I had one particular mentor who stayed with me. I'm always very grateful for what he's helped me achieve, both while I was at UC Davis and beyond.

What advice would you give to current engineering students?

The only advice I have for anybody pursuing education is to be curious. I think to be curious includes so many things.

To be curious means learning something new and acquiring new skills or new knowledge but being curious is a good approach to thinking about how other people think, and how there are different perspectives in knowledge and acquiring knowledge, particularly when we're with students or professors from different backgrounds.