Mountains Beyond Mountains

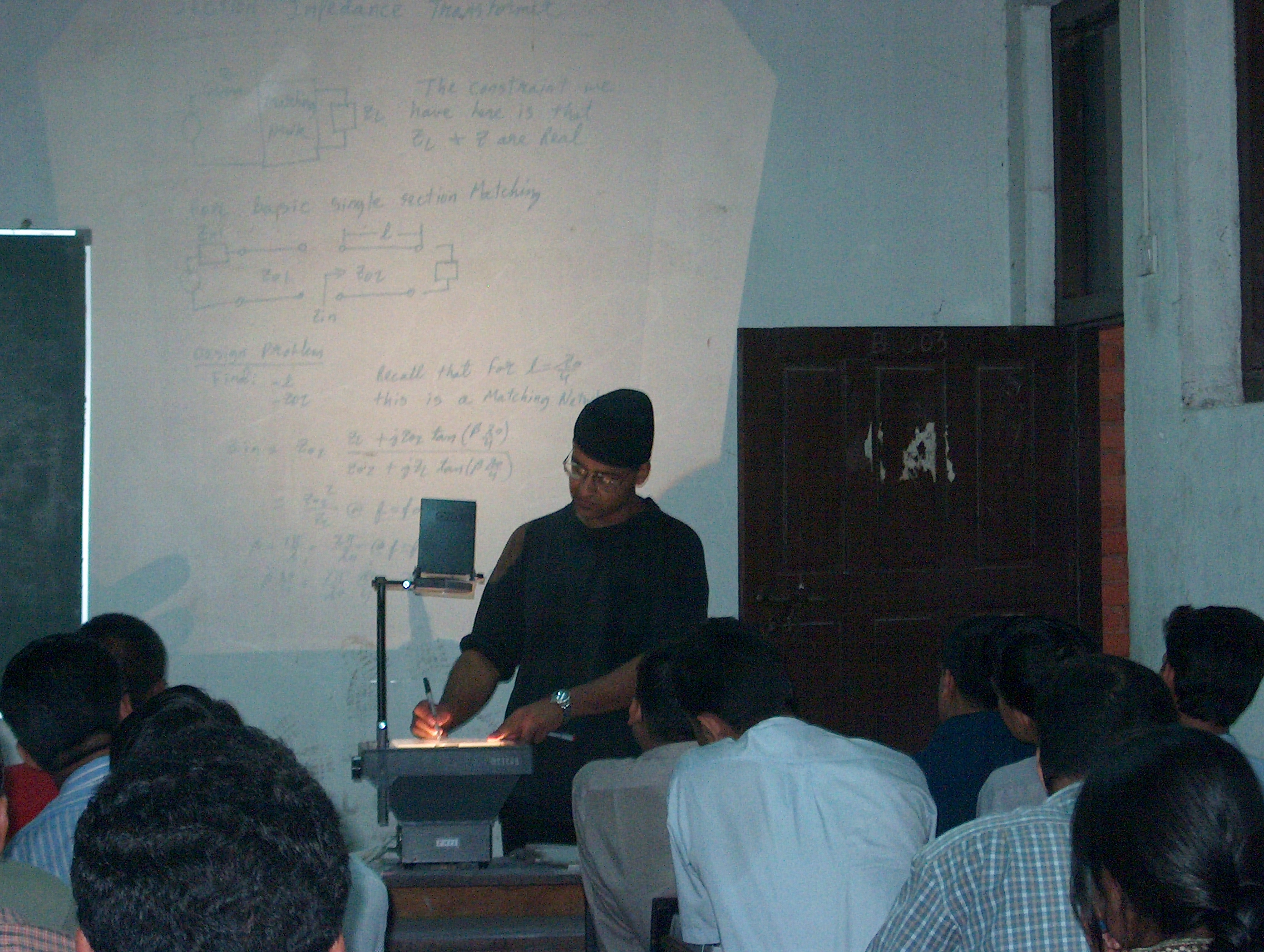

The Shared Legacy of a Nepalese Lab and Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering G. R. Branner

More than 7,500 miles separate Nepal and the University of California, Davis. That distance becomes imperceptible in a lab at Tribhuvan University in Kathmandu, the country's capital.

It all started in 2003 when Suresh Ojha, who received his B.S. in electrical and computer engineering in '93 and M.S. in '97 from UC Davis, quit his American electrical engineering job. He had received the opportunity to launch the first radio frequency, or RF, and microwave engineering lab in Nepal — where he was born — and couldn't turn the chance down.

"For the country with the highest mountains in the world, wireless infrastructure and wireless technology are key," said Ojha, explaining that the rugged terrain makes a network of physical communication cables too expensive to consider. "But in the early 2000s, Nepal didn't really have the technological basis to defend themselves when a vendor came from overseas marketing their wireless solution as best for the nation."

For Ojha, this lab was a once-in-a-lifetime chance to equip the nation with the skills to not only defend itself against opportunistic companies but also to establish a legacy of Nepalese electrical engineers who supported their country's effort in creating a wireless communications network.

When putting together the necessary materials for the lab, he quickly secured a large donation of equipment but was missing a pivotal component: he needed to create a robust curriculum to teach students with little to no familiarity with building circuits and transmitters to use these new tools.

"It doesn't take a long time to create a lab, but it takes a long time to create a course from scratch," he said.

Immediately, Ojha turned to one of his greatest heroes and former teacher, Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering G. R. Branner.

An Educational Blueprint

Ojha met Professor Branner by taking his EEC 132 series, a set of three courses that he developed in the 1970s and still teaches to this day.

The classes cover the theory and design of RF and microwave devices and prepare students for careers in industry, from designing phase-locked loops to system architecture. Ojha explained that the series changed his life.

"With the 132 series, Professor Branner has given students a blueprint for success in the electronics industry," he said. "That's not something that you expect to get when you take an engineering class, but that's what everybody walks away with when they take his courses."

Outside of the series' technical rigor and comprehensive approach to RF and microwave engineering, including access to some of the world's most sophisticated equipment housed in Professor Branner's lab, what really stood out to Ojha was its focus on applying engineering concepts to industry and a spirit for entrepreneurship. He isn't the only one to believe this, he explained, as companies in Silicon Valley often reach out to Professor Branner when they need to hire a new RF or microwave engineer.

"People in the industry know that if you find a Professor Branner grad, you know that that individual is going to be extremely skilled," Ojha said. "They can rely on that graduate to have a certain level of competence and work ethic to be very successful in whatever arena that they choose to go into."

With all this in Ojha's mind, there was no doubt that he wanted to model his course on Professor Branner's blueprint, so he reached out for advice. Professor Branner ended up sharing lecture notes and class materials to help him establish the lab's curriculum.

An Enduring Legacy

With the lab fully equipped and Professor Branner's blueprint, Ojha had everything he needed to create Nepal's first RF and microwave engineering program in 2003.

He taught the program at Tribhuvan University for one year before returning to the US, where he now works as a manager at the electronics test and measurement equipment company Anritsu. During his time as the course's professor, he modeled himself after Professor Branner, paying particular attention to establishing relationships with the country's pre-existing industry.

Now, twenty years later, the program continues strong. Recently, in Silicon Valley, Ojha ran into one of the students from the first class he taught at the lab. The former student recognized him on the street, saying that because of the experience, they were able to pursue a career in engineering that led them to a job at Apple.

For Ojha, this kind of trajectory would not have been possible without Professor Branner's generous contribution of his 132 teaching materials.

"Here is the impact of Professor Branner's legacy," he said. "His contributions have had a huge impact not just in entrepreneurship and innovation in Silicon Valley, but also half a world away in Kathmandu, Nepal."