UC Davis Students Win Grand Prize at 2014 iGEM Competition

by Derrick Bang

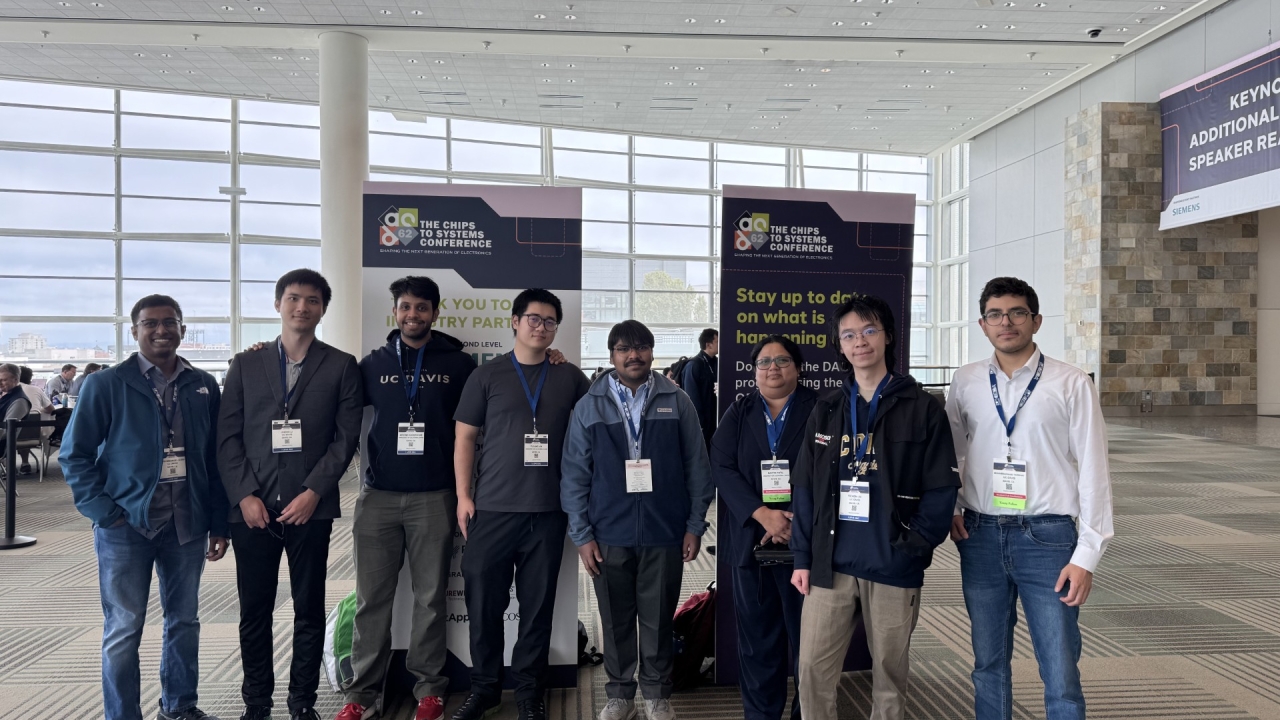

A team of seven UC Davis undergraduates successfully won the grand prize in the annual International Genetically Engineered Machines (iGEM) competition, which took place Oct. 30 through Nov. 3 at the Hynes Convention Center, in Boston, Mass.

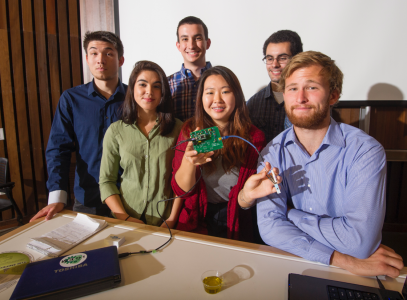

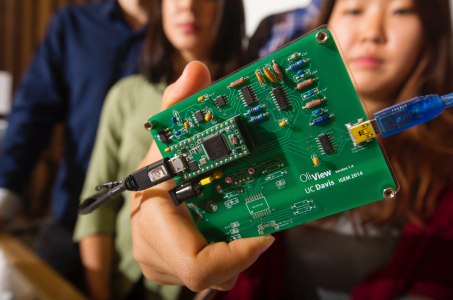

This triumph has directed all eyes toward the team’s breakthrough gadget: the OliView, a palm-sized biosensor designed to quickly evaluate the quality of olive oil.

The OliView’s obvious value undoubtedly helped the UC Davis students — Aaron Cohen, James Lucas, Lucas Murray, Sarah Ritz, Yeonju (Julie) Song, Simon Staley and Brain Tamsut — triumph amid a field of 245 teams from Asia, Europe, Latin American and North America. In addition to the grand prize, the Aggie team also won the Best Policy and Practices Advanced Presentation Award.

The team advisers include Selina Wang, research director of the UC Davis Olive Center; Marc Facciotti, an assistant professor in the Department of Chemical Engineering; Justin Siegel, an assistant professor in the Department of Chemistry; and Ilias Tagkopoulos, an assistant professor in the Department of Computer Science.

After contemplating various options during spring quarter, the UC Davis team settled on the olive oil challenge and began work in early June. They met with some of the largest U.S. olive oil producers, and attended a hearing at the California State Capitol, to better understand the precise nature of the problem.

“We also held an olive oil tasting at the Davis Food Co-op, and spoke to customers about how the oil’s health benefits decrease as the oil becomes rancid,” noted Ritz, a senior majoring in biochemistry and molecular biology. “We learned that if clear labeling could indicate the quality of the olive oil, it definitely would influence customers’ buying decisions.”

The undergrads soon realized that the challenge was quite complex, since it required the development of a gadget that could “read” and translate the elusive hint of rancidity — often a personal preference, from one consumer to the next, depending on the senses of smell and taste — into its chemical components. Until now, such tests have been time-consuming, crude and dependent upon expensive instruments, and the results often didn’t correlate with sensory traits.

“Our research led us to aldehydes, and we ultimately realized that we would need to detect the relative levels of this chemical class in olive oil,” explains Cohen, a senior majoring in biomedical engineering. “The design phase was full of setbacks. As one example, olive oil isn’t aqueous, so it basically destroys enzymes. We had to develop a protocol from scratch, which would allow us to measure the chemicals in olive oil, without denaturing our protein.”

The team worked hard during the past summer, and finally produced a working prototype that resembles an oversized thermometer, and — with attendant computer hardware and software — can read rancidity levels in a single drop of olive oil.

“It’s not perfect,” Cohen admits, “but we’re getting there.”

The team’s modesty notwithstanding, their OliView was “perfect” enough to take the top prize at iGEM.

“That was a total surprise,” Ritz said. “We never expected to win. We’re grateful for all the support we received from the university, as well as from people involved in the competition.”

“It’s important to note that the OliView isn’t yet suited to enforce quality standards,” Facciotti clarifies. “More work must be put into the chemistry and hardware. The concept’s core strength is that it can provide a common and readily accessible metric of quality, that can be widely distributed.”

At that point, the OliView could become a game-changer in a slippery conflict that has been percolating for years in the rapidly expanding U.S. olive oil market. Americans consumed 293,000 metric tons of olive oil in 2013, most of which was imported from European countries such as Spain and Italy. California growers are looking to take a luscious bite of that $5.4 billion industry; although they currently account for less than 1 percent of global production, their weapon of choice is a blend of skill and knowledge. California growers are convinced they can make a better product, and they also believe it’s high time American consumers woke up to the fact that — for example — most so-called Italian extra-virgin olive oil is neither extra-virgin, nor made in Italy.

More to the point, European olive oils have flunked taste and content tests often enough, in recent years, to be considered a culinary scandal. In July 2010, the UC Davis Olive Center released a report detailing the distressing news that 69 percent of the common imported oils sampled — and one of the 10 California-produced samples — failed to meet international or U.S. standards for extra-virgin olive oil.

When the UC Davis Olive Center released a second report in April 2011, the results were even more damning: Seventy percent of the imports failed at least one of the seven chemical lab tests, with 50 percent failing at least two tests. On a sensory note, fully 73 percent of the 134 samples failed taste and smells tests established by the International Olive Council (IOC).

Thus far, the standards set by the IOC and the USDA are voluntary, and therefore easily ignored. Bearing this in mind, and in response to the issues cited by the UC Davis reports, the California Department of Food and Agriculture just a few months ago announced its intention to require the testing and certification of olive oil, for purity and quality: a step that also would help consumers navigate descriptors such as “refined,” “virgin” and “extra virgin,” not to mention questionable terms such as “light” and “pure.”

No surprise, then, that these proposed regulations — along with the research reports from the UC Davis Olive Center — have been disparaged by the North American Olive Oil Association, which represents importers, and by the IOC, whose members make up 97 percent of the global production of olive oil.

These entities likely will find their arguments seriously diminished, once the OliView is made available to olive oil producers, buyers and retailers.

‘Their project has great potential,” said David Garci-Aguirre, production manager of the Lodi-based Corto Olive Co., in a recent UC Davis News Service press release. “A biosensor that provides an easy, affordable way to help ensure the quality of our olive oil could prove incredibly useful: an innovation that would help get good oils into the hands of those who are trying to buy good oils.”

“It’s especially rewarding,” Tamsut concludes, “knowing that our project is practical, and will solve a real, tangible problem.”