UC Davis Professors Bring Chemical Engineering Back to its Whiskey Roots

For UC Davis Chemical Engineering Professor Greg Miller, a new course began with a single sip.

While tasting whiskey with friends, he noted an unusual peppery flavor and became curious how it was produced. The more he looked, the more he realized that there wasn’t an easy answer, as most whiskey distillers rely on tried-and-true recipes instead of science.

Several years and a lot of research later, Miller and Chemistry Professor Mike Toney now teach the “Chemical and Engineering Principles in Whiskey and Fuel Alcohol” (ECH/CHE 168) course at UC Davis, which teaches undergraduate students the chemical engineering and chemistry of making whiskey.

“It’s a way to connect a lot of dots,” said Miller. “We go through every single step of the whiskey-making process from grain to finished product, teach them the mechanics of it in the lab and then give them lectures about all the chemistry and how it contributes to flavor.”

Back to its Roots

Chemical engineering and whiskey have a shared history. In the 19th Century, whiskey was the biggest chemical industry in the U.S. and producers were forced to innovate to make their product faster and more efficiently. This drove advancements in the field of chemical engineering, and many of the basic concepts students learn to apply to oil and other industrial products were developed for alcohol.

With ECE/CHE 168, Miller and Toney are bringing the field back to its roots to show chemical engineering and chemistry students how their knowledge applies in a fun, new context.

“It’s probably the oldest chemical engineering industry there is and there’s a lot of basic stuff to be learned from it—how to optimize your fermentation and distillation and the chemistry behind them,” said Toney. “There’s also a lot of chemistry and chemical engineering to be learned from this type of practical subject that you don’t necessarily get taught in textbooks or other classes.”

From malting the barley to aging, each step of whiskey-making can introduce or amplify different chemicals that can enhance or ruin the flavor of the final product. These changes happen on a level almost undetectable in the lab, but the human nose and tongue are much more sensitive and can notice the difference in the final product. Therefore, making good whiskey means being aware of what’s happening chemically at every turn.

“It’s like a cooking operation,” said Miller. “There are maybe 10 steps, and each of them puts a little fingerprint on the chemistry of what comes out at the end. You need to do this major element separation in a way that respects the trace elements, and the students have never had to think about it that way.”

Chemistry at Every Step

Whiskey is mostly just water and alcohol, but what makes each brand and style different is chemistry and engineering.

“You don’t need science to make good whiskey,” said Miller. “What you need the science for is when something goes wrong, or how to make it better, or if you have a certain flavor profile and you want to nudge the process to be something else.”

On day one, the students receive a bag of barley that they malt at home and bring back to class for chemical analysis. Over the next few weeks, they look at things like the diastatic power of the malt—its ability to break down starches into fermentable sugars—the phenolic content of the kilned malt, which affects the flavor, as well as the amino acid content, which is important for fermentation.

With this knowledge, the students can optimize and run the fermentation and distillation processes using a similar but legal solution. Finally, students study how to make different esters, the good-smelling aromas created by combining carboxylic acids and alcohol during the aging process.

“You get ester formation in the aging of spirits,” said Toney. “When they’re aged in barrels ester formation adds to the good kind of volatile smells in aged spirits.”

At the students’ request, Miller and Toney also make sure to cover the business side of whiskey-making, which is something most chemistry and chemical engineering majors typically don’t have to think about.

“We’re not giving them business plans, but we’re trying to share information that any potential entrepreneur might want,” said Miller. “[The students] haven’t really thought about the economics of any commodity this way.”

Distilling for the Future

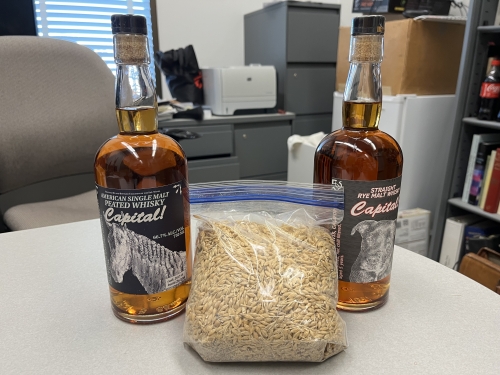

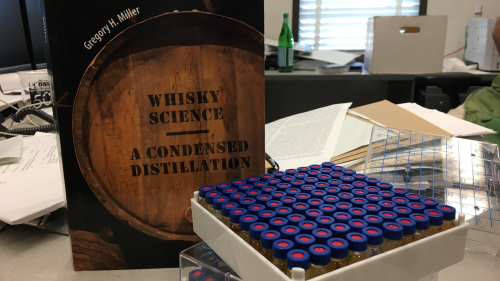

As Miller became more curious about whiskey science, he spent several years researching the topic and penned Whiskey Science: A Condensed Distillation in 2019. He also leveraged his engineering background to become Yolo County’s first licensed distiller and began to make rye and single-malt whiskeys that have been well-received and sold in local liquor stores.

“The book and this distillation project are all in support of research and teaching on campus,” said Miller. “It’s practical, people like it and I’m sharing that with our students through the class.”

Meanwhile, Chemistry Professor Mike Toney and a friend were thinking about starting their own distillery and found Miller through a list of licensed distillers in the area. Though the business never came to fruition, Toney and Miller became friends and started developing the course together.

Since launching as a pilot class in 2018, ECH/CHE 168 has become such a popular elective that it has developed a long waitlist. The two hope to continue developing the class and add more sections to accommodate the demand.

“Now [our students] can go into a bar and be the smartest people in the bar for the rest of their lives,” Miller joked. “We’re doing them a service.”