UC Davis biomedical engineers and veterinarians collaborate to regrow bone

Amphibians and starfish are known to regenerate their limbs; lizards can partially re-grow their tails. Thanks to the combined efforts of surgeon/professors at UC Davis’ William R. Pritchard Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital, and biomedical engineers at the campus’ Translating Engineering Advances to Medicine (TEAM) facility, one of nature’s wonders has become a breakthrough medical miracle equally adaptable to mammals.

On May 15, Sacramento’s CBS13 aired a poignant news feature devoted to how the lives of canine patients are being improved by these collaborative UC Davis researchers. Hoshi, a Montana-based grey speckled collie, enjoys a renewed quality of life thanks to a regenerated lower front jaw; Lad, a collie from Kentucky, soon will have an entire replacement lower jaw.

The surgical procedure was developed by biomedical engineer Dan Huey and veterinary surgeon Boaz Arzi, while both served as postdoctoral researchers in a lab overseen by Kyriacos A. Athanasiou, a distinguished professor and chair of the UC Davis Department of Biomedical Engineering. Working with the UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine’s Dr. Frank Verstraete, Huey and Arzi refined the technique, which involves removing the diseased or damaged jawbone, and then filling the resulting cavity with a precisely measured titanium plate that holds a special sponge soaked in bone morphogenic protein. Over a period of eight to 10 weeks, this sponge-filled “scaffold” induces the remaining jawbone to grow new bone cells.

Result: a happier, healthy dog that regains her well-shaped facial characteristics.

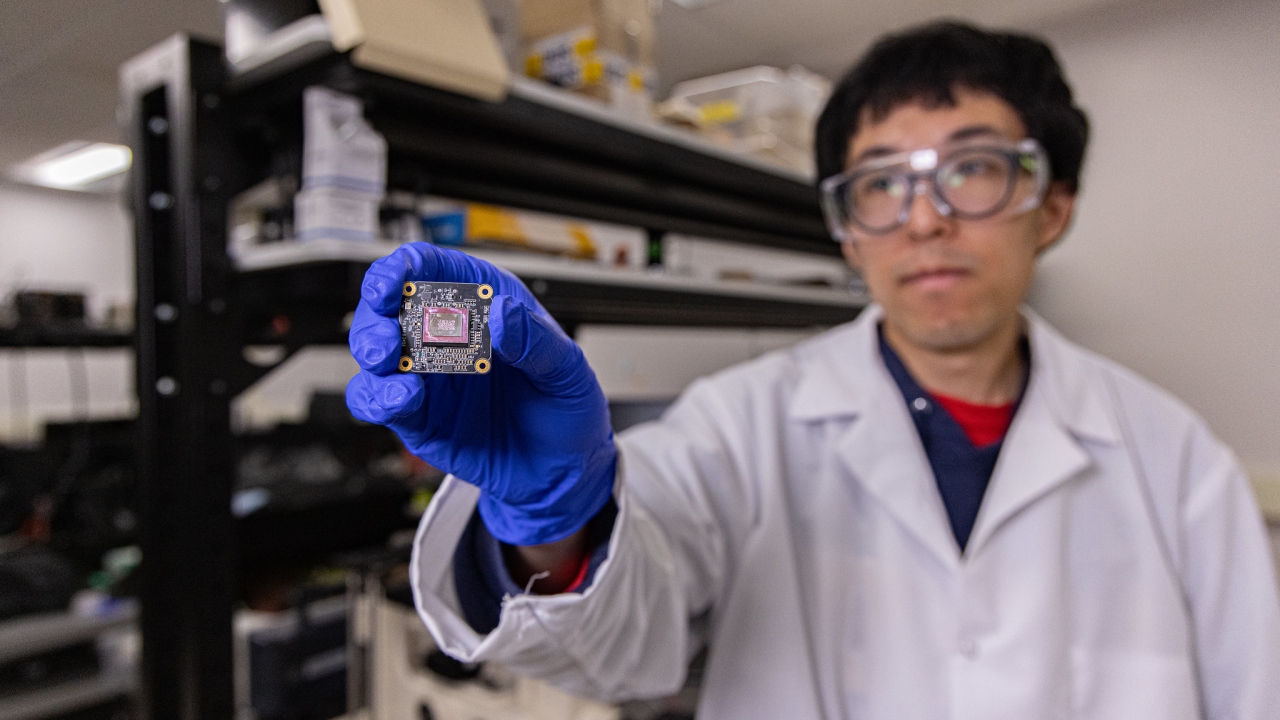

This revolutionary procedure is augmented further by the morphological precision enabled by the TEAM lab staff, overseen by Athanasiou and assistant directors Marc Facciotti and Jerry Hu. Thanks to fabrication and prototyping equipment that includes NextEngine 3D scanners and Polyjet 3D printers, Lucero and his colleagues are able to craft precise models of the patient’s entire skull and proposed replacement jaw, which allows the crucial titanium scaffolding to be prepared prior to — rather than during — the already complicated surgery. Aside from granting everybody involved plenty of time to fine-tune this metal plate as precisely as possible, the surgical procedure itself requires less time, and therefore is less dangerous to the canine patient.

Looking ahead, this collaborative procedure has the potential to offer similar benefits for people who suffer from various forms of bone cancer, or who’ve been in disfiguring accidents.

“There’s a good possibility this may spill over into human reconstructive surgery,” Dr. Verstraete acknowledged, during the CBS13 news report.

Many pet lovers first learned of this procedure back in August 2012, when it was employed to give a healthy new jawbone to Whiskey, a 60-pound Munsterlander who lives in San Francisco. Since then, subsequent canine patients from around the world have come to UC Davis in hopes of restoring damaged jaws, and have included three full-arch re-growth surgeries and more than a dozen partial re-growths, all of which have been successful.