Bruno Carciofi Cooks Up Food Engineering Research from Cold Plasma to Hot Ovens

When considering what interested him in food engineering, Bruno Augusto Mattar Carciofi talks about growing up close to his Lebanese grandmother in Brazil, who was constantly in her kitchen cooking.

"She was always working at home, making different foods from scratch," said Carciofi, who joined the Department of Biological and Agricultural Engineering at the University of California, Davis, as an assistant professor in July. "In her culture, they had these different ways to add spices, and the smell was so unique in that house. That was the first moment I saw processing happen."

He admits that he wasn't entirely sure what food engineering was when he was considering what path of study to pursue, but it was at the intersection of his interests — he loved chemistry and math as a student, and food was an essential part of his home life. Carciofi dove in and found that learning about food on a chemical level and how it is processed felt natural but was also a challenge.

A Recipe for Success

Carciofi earned two bachelor's degrees, one in food engineering and the other in chemical engineering. His master's and doctoral degrees are also in food engineering. Both are from the Federal University of Santa Catarina, which is the top-ranked university for food science and technology research, and U.S. News & World Report ranks in the top 100 schools globally.

Before joining UC Davis, Carciofi was an associate professor at his alma mater since 2010. During his professorship, Carciofi notably earned several best conference paper awards. His paper on "Mathematical Modeling of the Bacterial Kinetics in a Microbial Fuel Cell Inoculated with Marine Sediment" earned best conference paper in 2014 at the Brazilian Society of Chemical Engineering.

He also earned two sequential awards from the Brazilian Society of Food Science and Technology: the 2016 Best Conference Paper on Food Engineering for his work on achieving crispy, oil-free potato chips via vacuum microwaving and the 2018 Best Conference Paper overall for his research on developing a measurement system for analyzing acoustic data as indicators of food crispiness.

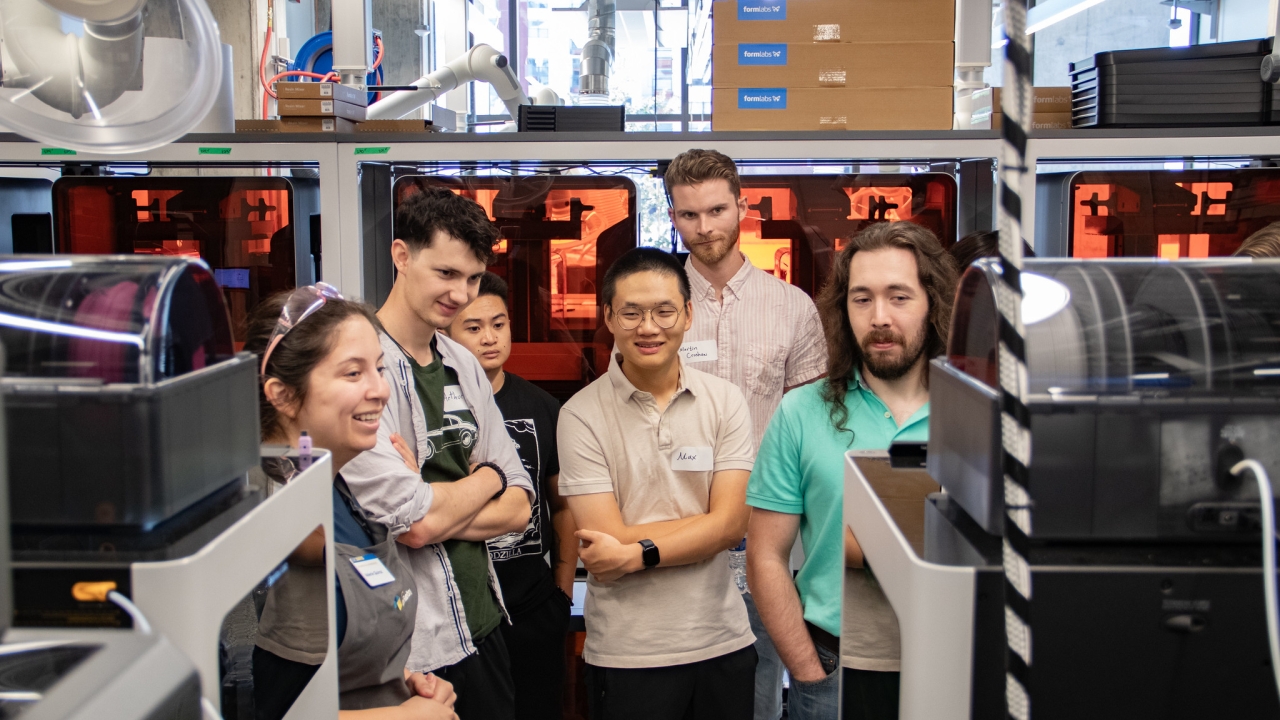

While he has excelled in his research in Brazil, Carciofi feels that joining the faculty at UC Davis is ideal for going further in his field, owing mainly to the multidisciplinary ethos of the university and the College of Engineering in particular.

"It's different from other departments I've found around the world," Carciofi said of UC Davis' biological and agricultural engineering department, which U.S. News & World Report ranks No. 1 for undergraduate and No. 3 for graduate agriculture engineering programs.

"When I'm here, I can discuss more multidisciplinary aspects with people," Carciofi continued. "For example, with foodborne bacteria, sometimes I cannot fully understand exactly how one process differs from another in terms of inactivating those cells. I would need someone who can use molecular biology tools to investigate intracellular aspects such as gene expression."

Digging into Food Processes to Grow Progress

Carciofi is researching high-intensity pulsed light and cold plasma technologies as potential non-thermal ways of inactivating bacteria or slowing their growth. These technologies could be applied to food surfaces to reduce issues with bacterial contamination.

This could be particularly beneficial in processing something like raw meats. Uncooked meats can carry harmful bacteria that have the potential to cause diseases if not cooked or handled properly. However, if the bacteria isn't there at all, or its growth has been significantly slowed, its risk could be greatly reduced.

Cold plasma technology could also be applied to breaking down biological waste products from the agrifood sector. Carciofi is looking forward to being close to the university farms and researchers who work in renewable resources to collaborate on this research.

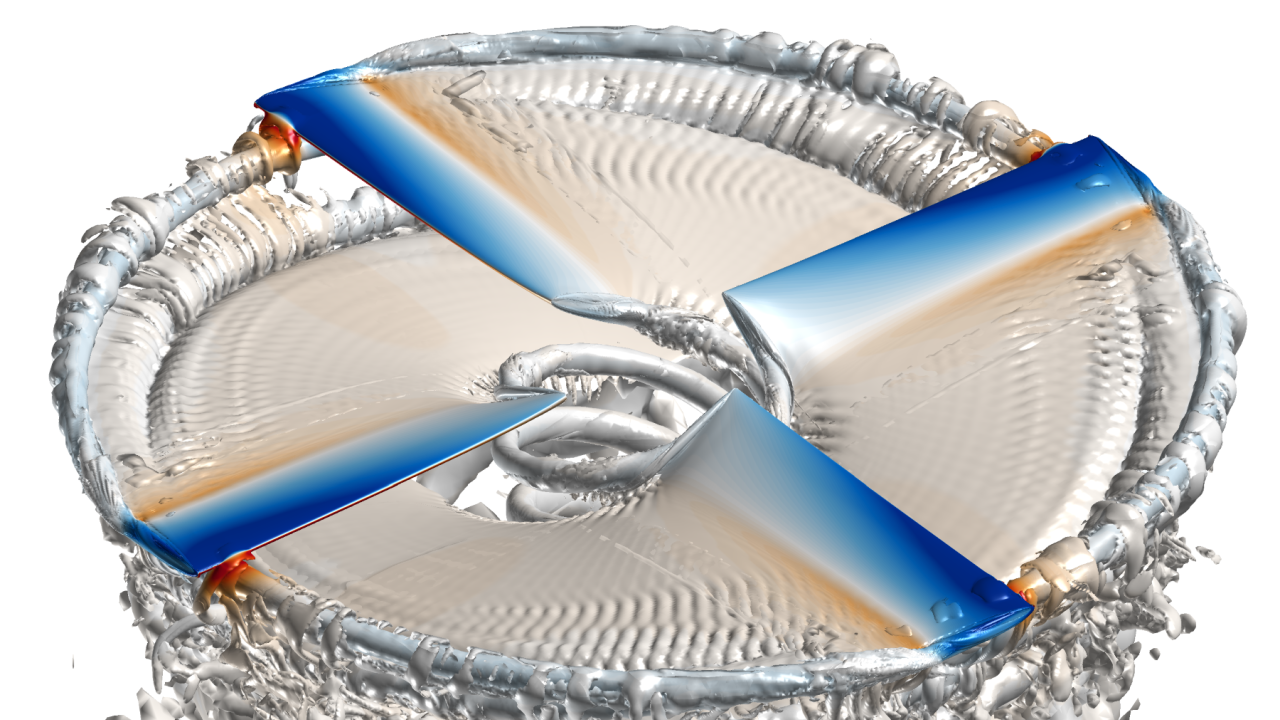

In his lab, Carciofi will also be researching modeling for the physical and chemical changes to foods under processing, including cooking in ovens, a project with the oven manufacturer Whirlpool he began in Brazil.

"If we are calculating the color and browning throughout the roasting process, we can describe it based on the heat, the moisture transport, the cooking time, the local temperature, the chemical reactions," said Carciofi. "Instead of going to the lab and cooking a lot of meat, we can run the simulation on the computer."

Carciofi says modeling of this type and at this scope is not something that food scientists have expanded on much yet, and it is something he is excited to dig deeper into.

Eventually, Carciofi hopes to build models that can help optimize oven design for energy efficiency, so future cooks won't necessarily have to have their oven on all day like his grandmother did. Even though, for Carciofi, watching her constant process was the foundation of where he is today.

"The kitchen was doing something 100% of the time," he said. "The processing industry on a small scale started that way because it was really pragmatic, and everything was well done."