Scott McCormack Impacts Classroom and Community with 'Materials Science for All' Philosophy

Since joining the University of California, Davis, in 2019, Scott J. McCormack, an assistant professor of materials science and engineering, has been on a personal quest to make materials science more accessible to more people through teaching, mentorship and outreach.

His efforts have not gone unnoticed. In 2021, McCormack received a National Science Foundation CAREER Award, a prestigious grant for early faculty. The American Ceramics Society, or ACerS, has recognized him for his outreach to and revitalization of the scientific society's Northern California chapter. Last spring, he was celebrated for his exceptional performance in the classroom with an Excellence in Teaching Award from the UC Davis College of Engineering.

Some of the CAREER award supported advancements in McCormack's research focusing on computational analysis and ultra-high temperature experiments on ceramic systems. McCormack also used the funding to host a seminar to teach high school and middle school instructors how to introduce and teach materials science in their classrooms.

Living in a Materials World

Five teachers from area schools attended the inaugural seminar, held last fall at the UC Davis MESA Center, which provides college-prep programming in math, engineering and science. McCormack began the seminar by asking the teachers to notice material innovations in the room like the steel beams holding the building together and the semiconductors in their smartphones.

Materials science, McCormack pointed out, is not just all around us; its innovations have fundamentally changed human society, from the pottery and plastic used to hold, transport and preserve food to the quartz crystals in watches and clocks that enabled a growing global society to interact with each other and eventually led to GPS tracking.

"I want to highlight that no matter what engineering field you work in, they all touch materials," he said. "If you're a civil engineer, you could be working with novel types of cement. If you're a mechanical engineer, you may be interested in materials that have high strength-to-weight ratios. I want to highlight to the teachers that if you want to be the ones developing these next-generation things, it is the material scientists who are pushing the edge."

The instructors then participated in several experiments designed to be used in a classroom setting as hands-on ways of explaining materials science. One such experiment, titled the Candy Fiber Pull, had the teachers melt Jolly Rancher candies in a beaker into a liquid state and pull the candy fibers apart. The candy is meant to simulate the production of glass-like fibers from a liquid to a solid form.

The workshop was extremely successful, and McCormack plans to host it annually. At this year's workshop, he hopes to hear feedback on taking the experiments into the classrooms. The experiments are packaged together as kits that instructors can purchase for their classrooms through ACerS, of which McCormack has been an active member since 2015.

Rejuvenating the ACerS Northern California Chapter

Reflecting on his affiliation with the organization, McCormack infers that his role on the ACerS Presidents Council of Student Advisors, or PCSA, which he held while he was in graduate school, was instrumental in his appointment at UC Davis. It trained him in leadership and helped establish connections in the materials science community, reinforcing the importance of mentorship for an early-career scientist.

Seeing the value of establishing connections and bonds between young materials scientists, as well as industry professionals and potential mentors, McCormack took on the role of mentor-at-large to the PCSA this year. During his four-year term, he will help the current PCSA members access resources and interface with the industry professionals in the organization.

"It's the fun part of my job," he said. "It is also about giving back to the community, and enabling the students to become the best that they can become."

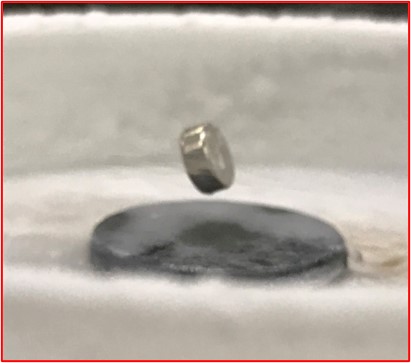

McCormack, shown crouched, shows superconductivity to middle and high-school-age students as the president of while chair of the American Ceramic Society’s President Council of Student Advisors in 2018. (Courtesy of McCormack)

He has also been instrumental in reinvigorating the NorCal chapter of the society, which was largely dormant until he joined UC Davis and saw the need for connecting with industry. Getting the chapter back on its feet during a global pandemic, however, presented an unforeseen layer of obstacles; institutions like ACerS relied heavily on in-person gatherings. McCormack worked around it, hosting a series of webinars, including a diversity and inclusion event and one on batteries that maxed out the number of people you could have on a Zoom conference.

"After several years of inactivity, the Northern California chapter of ACerS has become one of the most active in the country, thanks largely to the tireless effort of Professor McCormack," said James Shackelford, a UC Davis Distinguished Professor Emeritus of materials science and engineering renowned for his research on glass.

Teaching for Life After the Classroom

McCormack also exercises tireless efforts in the classroom, as recognized by his Excellence in Teaching Award. Drawing from his own education in Australia, McCormack has approached his undergraduate classes — thermodynamics and kinetics, which he describes as math-heavy and not straightforward — with a tiered learning structure that leads to solving open-ended problems. This tactic, he believes, sets them up for early success in their careers.

For instance, one open-ended problem he poses to his students is a scenario in which they are working for a construction company in blisteringly hot Arizona. The students are asked to recommend materials to use that will keep homes at a pleasant temperature. They have 10 pages to present their recommendation, and they must use thermodynamic and kinetic principles.

"That's what the real world is going to be like," said McCormack. "There's no recipe for life, right?"

There may not be a recipe for life, but McCormack's approach to teaching and mentorship sets a foundation of confidence in his students and mentees, so they can leave his classes and mentorship knowing how to think for themselves and come up with their own answers. He wants to give them the tools they need to leap into the big unknowns of research and life having learned how to handle the hard questions.

McCormack even has tangible evidence that his method works: handwritten letters from some of his former students.

"Some of the letters were like, 'Thank you for making the class challenging,' and 'Thank you for making me realize what life was like in a real job.' I enjoyed those."