Horizon Lines

Building a Living-Learning Lab for Sustainable Transportation Research

In the late 1960s, Davis, California, paved the way for bikeable cities in the United States through innovative biking infrastructure.

It became the first place in the country to install a bike lane on an existing city street in 1967, setting the design standard in the process. The regulations the City of Davis developed through this project and the other bike lanes that quickly followed (think: how wide the lanes should be or how to incorporate them into intersections) caught the attention of the California Department of Transportation, or Caltrans, using them as inspiration for the state’s first-ever bike infrastructure guidelines.

Nearly 60 years later, the city continues to build on its legacy of being a model as the country’s biking capital. Yet, there has been little research exploring why its infrastructure — spanning more than 100 miles of interconnected bike lanes — is so successful and how other cities, big and small, could scale similar designs.

“We've built better bicycle infrastructure than anywhere else in the United States on a per-mile basis,” said Kari Watkins, a leading expert in bicycle infrastructure research and an associate professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of California, Davis. “Once you get outside of California, people have no idea about what is here in Davis and how big of an impact it's had.”

Watkins hopes to change all of that. She is leading a project to instrument the campus and city with sensors to turn Davis into a one-of-a-kind living-learning lab for bicycle infrastructure research. The project also looks at how Davis’ bike infrastructure interacts with the Unitrans network — the UC Davis transit system — and how to optimize bus routes to improve sustainable transportation options in cities.

The Reality of Bike-Ability Research

Researchers often struggle with assessing bike infrastructure simply because of the lack of data.

“It's incredibly difficult to get data about cyclists’ interactions with vehicles and pedestrians and things like that because there are so few cyclists in most places,” Watkins said. “Davis is one of those really unique places where we can observe it because of how many bikers there are.”

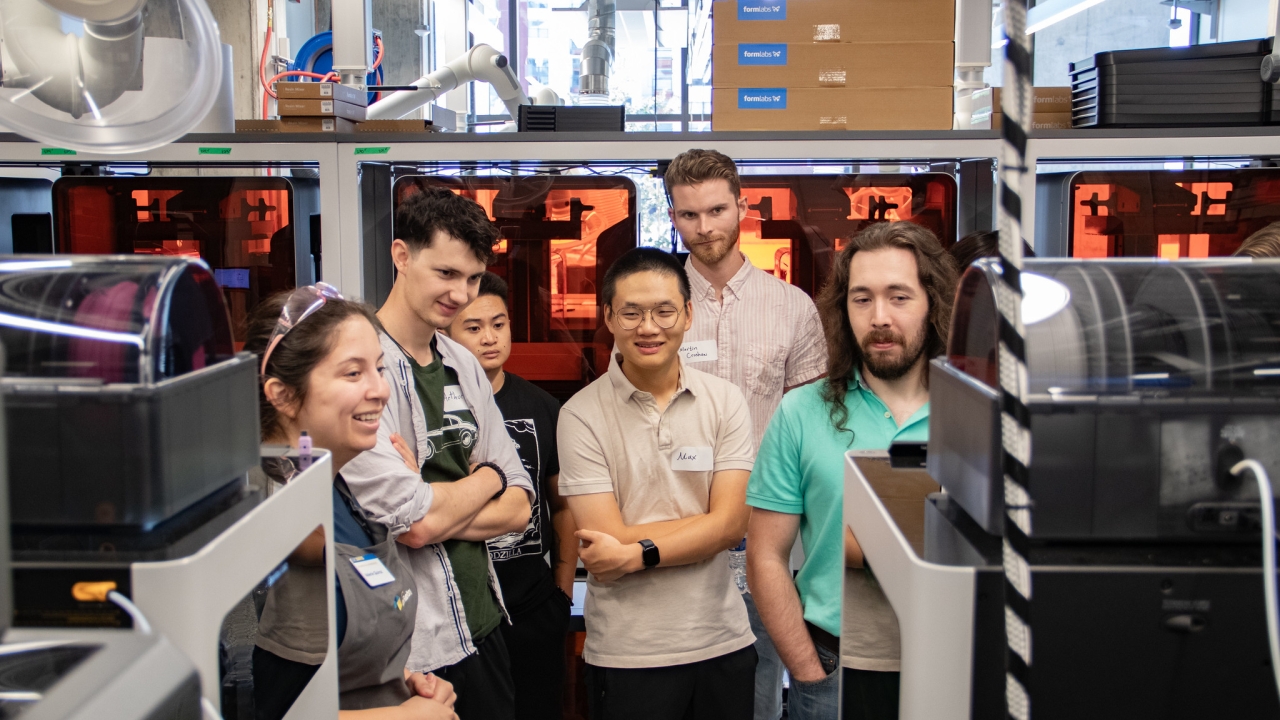

Watkins and her team, which includes Dillon Fitch-Polse, the director of the BikePlus research center at the UC Davis Institute of Transportation Studies, consulted with Professor of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering Iman Soltani, who specializes in developing machine learning for estimation tools, to identify the best methods and sensors to capture cyclist interaction data.

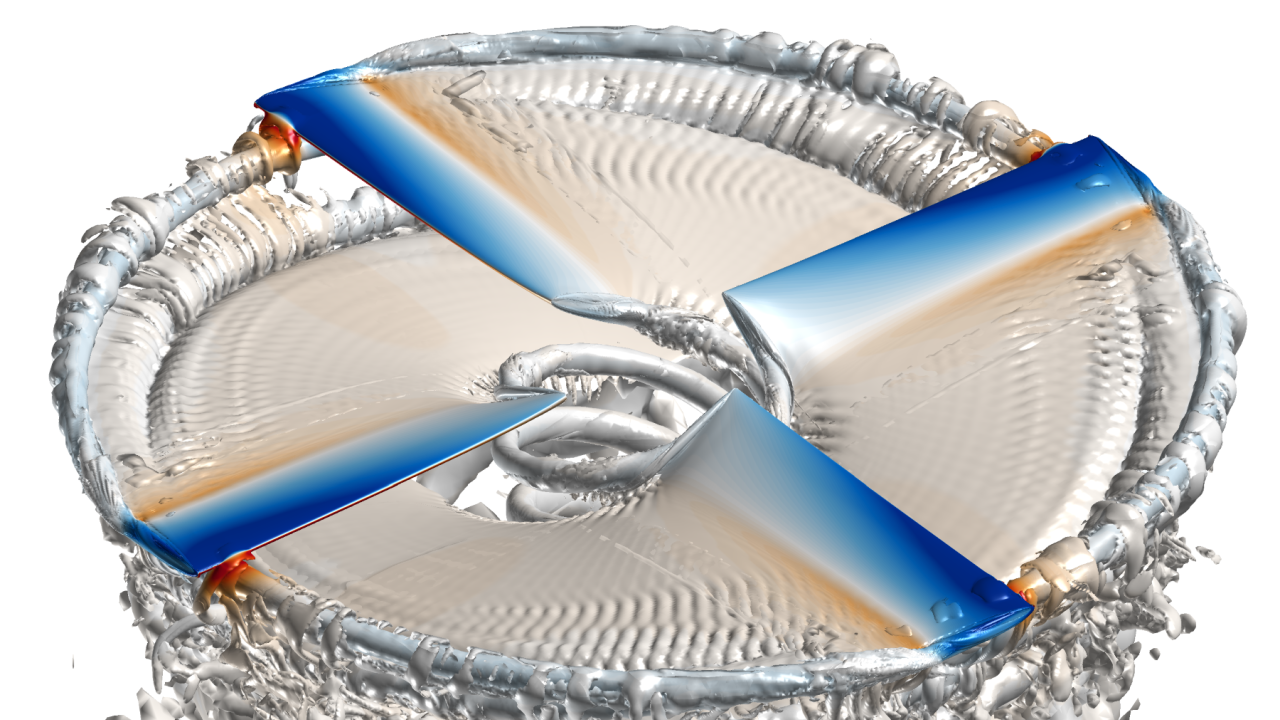

Ultimately, the team selected state-of-the-art sensors from VivaCity, a UK-based smart traffic monitoring company. These AI-powered computer vision sensors rely on video footage to extract information and are notable for their ability to track cars, cyclists, e-scooters and more, offering accurate insights into traffic patterns, speed averages and even near-miss incidents.

Near misses are a particularly interesting phenomenon to Watkins and one that she thinks Davis is well-placed to collect rich data on. This is mainly due to the number of bike roundabouts on campus open to bicyclists, buses, pedestrians and more.

“One of the most fascinating parts about campus is that a lot of people have these close-call incidents, but because we're all moving slowly, because we're biking, walking and things like that through the intersection, most incidents do not turn into something major unless there's a car involved.”

Watkins and her team will place the sensors at high-traffic intersections across campus, such as the bike roundabout near the Silo on California Avenue, to observe trends and make suggestions for improved safety. Once the safety additions are installed, Watkins will collect new data to assess its effectiveness.

“What does it mean to be bikeable from an analytical standpoint? That's the void we're filling. We’re instrumenting Davis with these sensors so we can collect better data about bikes that we can use to improve the campus and City of Davis, but also to send this knowledge about design to the rest of the world.”

Fueling Research

The other part of this research initiative leverages a tool Watkins co-developed while pursuing her Ph.D. at the University of Washington. Called OneBusAway, it is an opensource app that provides real-time information about transit vehicle arrival times to both riders and researchers.

To bring OneBusAway to Davis, Watkins partnered with the student-run Unitrans to use their vehicle location data on all the buses in their fleet.

“With Unitrans, we have such a unique transit agency in town because of its history as a student-run agency and the fact that it still only has a handful of full-time employees, and everyone else is an undergrad. It’s a pretty nimble agency that has the ability to be super innovative because there’s not a lot of red tape.”

With this vehicle location data, Watkins’s team can research factors that might slow operations and make buses less reliable within the Unitrans network. For example, her team will be looking at West Village, which is notorious for crowding, or when a bus falls behind schedule due to the high number of passengers boarding and disembarking.

“Once we've got pretty good data about how behind those groups get and how full those buses are, we can start to do new research on the crowding impacts of operations, which not many people have done.”

At the Intersection of Transit and Health

The immediate benefit of optimizing bike infrastructure and reducing things like slowdown in bus systems is to make sustainable transportation more accessible and reliable. While less direct, these improvements to transit infrastructure could also improve public health outcomes.

“There are ties between vehicle use and a lower incidence of people getting recommended physical activity amounts,” Watkins said. “We know that having people be more active is one way to improve public health, and so making more bikeable cities where people can use a bike for transportation is one way to vastly improve our activity levels and the positive outcomes associated with that.”

People who use buses also tend to be more active than those who don’t, as they have to walk to access stops, Watkins noted. With the promise of fewer cars on the road and less carbon dioxide emissions, the greater use of sustainable transportation modes also poses excellent environmental benefits, particularly to air quality.

The Next Stops

With a project as large as a living-learning lab, there are many developing avenues the research can take.

In addition to the partnership with Unitrans, Watkins and Fitch-Polse are working with Caltrans on the use of sensors similar to those in the living-learning lab project. Not unlike 60 years ago, the state transportation agency is interested in the data from cities like Davis to understand the impacts of biking infrastructure and to improve what’s already been built in major California cities in the years to come.

Similarly, once more information is collected from the AI-enabled sensors about cyclist interactions, Junshan Zhang, a professor of electrical and computer engineering, will use Watkins’ data to advance automation in driverless vehicles, improving their awareness of cyclists on the road.

One project that Watkins is particularly excited about is an online master’s degree in sustainable transportation. While in the early stages of its development, the program would offer classes on bike-ability, transit planning and operations and electric vehicles and would require students to come to campus a few times throughout their degree to engage with and contribute to the living-learning lab on campus.

Perhaps more than the others, this online master’s program helps evince the horizon line where all the research projects come together for Watkins: turning UC Davis into the global leader in bike and bus research.

“Davis has achieved what bike advocates implore cities should do. Not that we're perfect; there are still many things that we can even improve in Davis — designs of intersections as an example — but we're so far ahead of many communities. It’s a great place for people to come and see as an example of how they could be designing.”

Learn about how we transform mobility