A Second Wind

A new wave of engineering faculty builds on the college’s wind tunnel legacy to take aerospace research at UC Davis to the next level

Case van Dam, professor emeritus in the Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, remembers sitting in a meeting in Bainer Hall in 2005 when his cell phone rang. It was his Ph.D. student, Jonathan Baker, on the line. Baker was conducting a wind tunnel experiment with a new design of airfoils and something big was happening.

"He said, 'Professor, I think there's something wrong with the tunnel. The airflow keeps on lifting more and more,'" said van Dam. His meeting ended, and he went to see what was going on.

"I said, 'Jon, I think it's doing what the computations are indicating.' It was just lifting to a much higher level than anyone had seen before," he said.

The research was published, and a year later, Sandia National Laboratories built a larger version of that model to test on a small wind turbine. "And as I'm standing there," van Dam recalled, "there are two industry engineers from some large company, and one says to the other, 'That is the shape of the future.'"

They were right. That airfoil design for turbine blades was adopted widely throughout the aeronautics and aerospace industry. And that story is but one example of the type of cutting-edge, impactful research that has resulted from wind tunnel experiments at UC Davis.

The Golden Age of Wind Tunnels

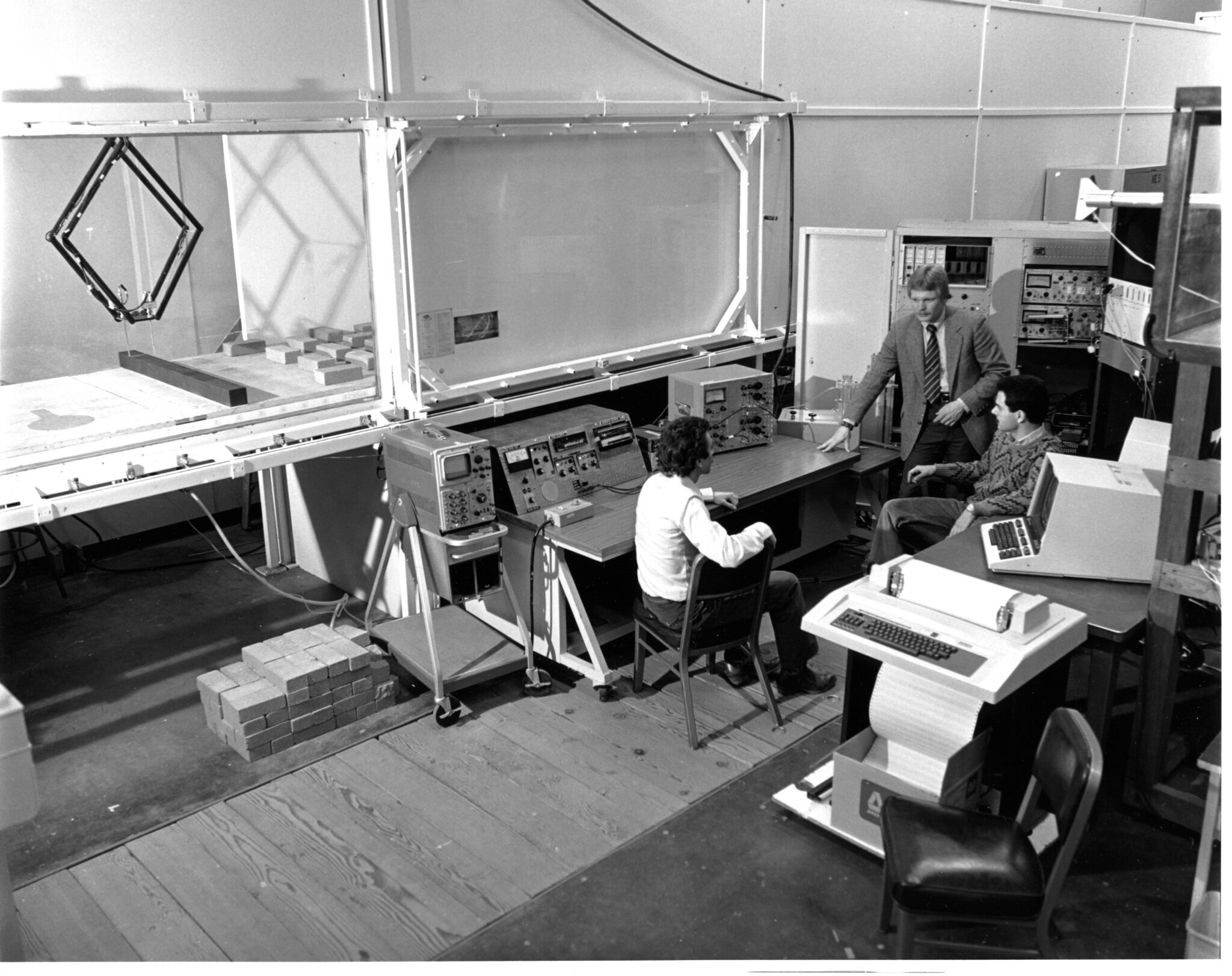

The university's first wind tunnel, the Atmospheric Boundary Layer, was built in 1975 inside Bainer Hall by then-new faculty member Bruce White in partnership with Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. The Aeronautical Wind Tunnel, or AWT, of van Dam's fond memory was installed in 1997 where both wind tunnels now live, in an annexed building in between Bainer's north and south wings.

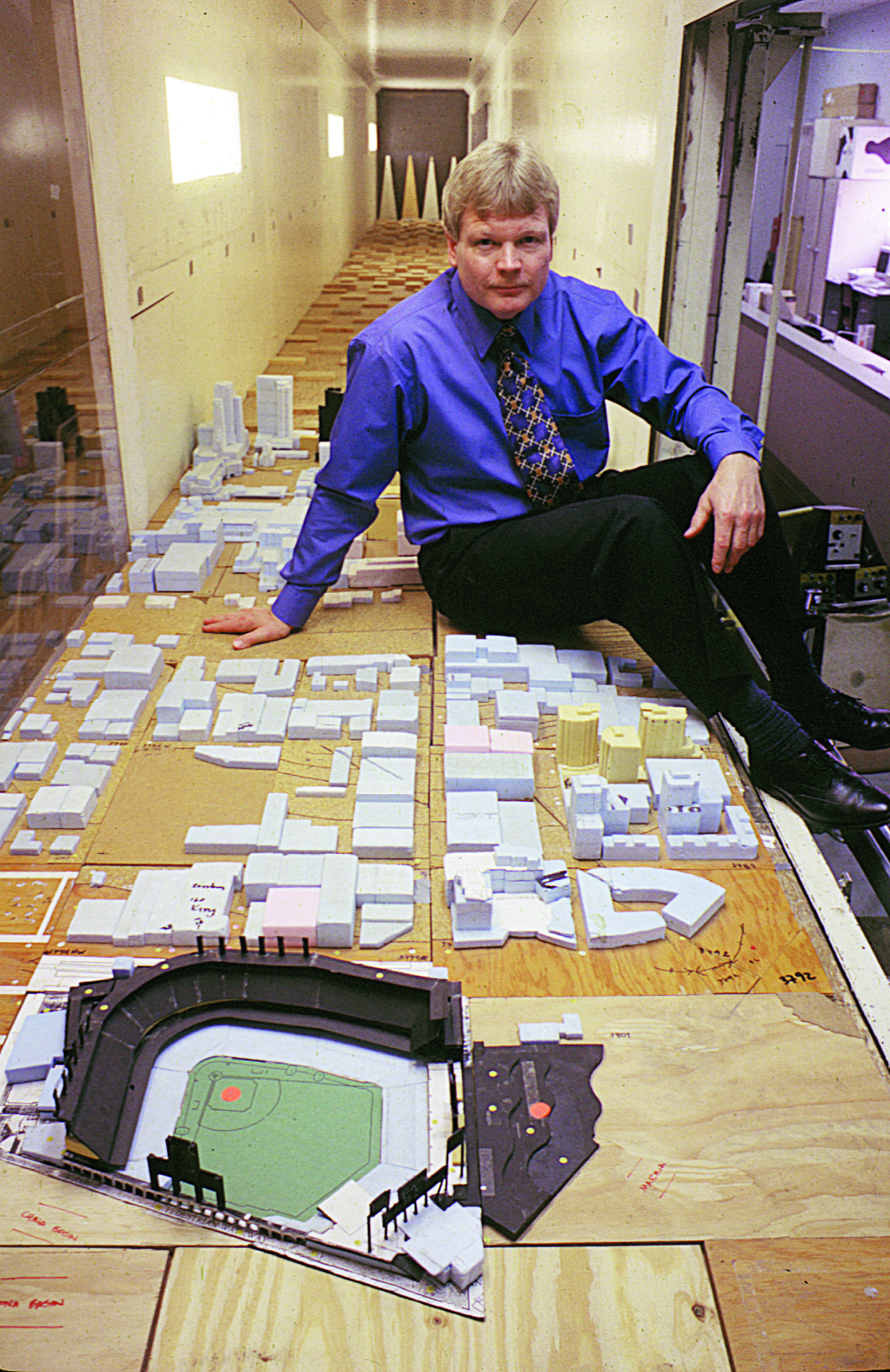

During the early '90s into the early 2010s, White and van Dam, and their graduate students produced progressive, innovative research. In addition to the aforementioned contributions to the industry, White famously recommended the San Francisco Giants rotate their new stadium 180 degrees based on wind experiments in 1995, and UC Davis wind tunnel experiments simulated Mars' corrosive, sand- and dust-blown surface to inform NASA's hardware designs for missions to the red planet, to name a few.

A Changing Wind Blows

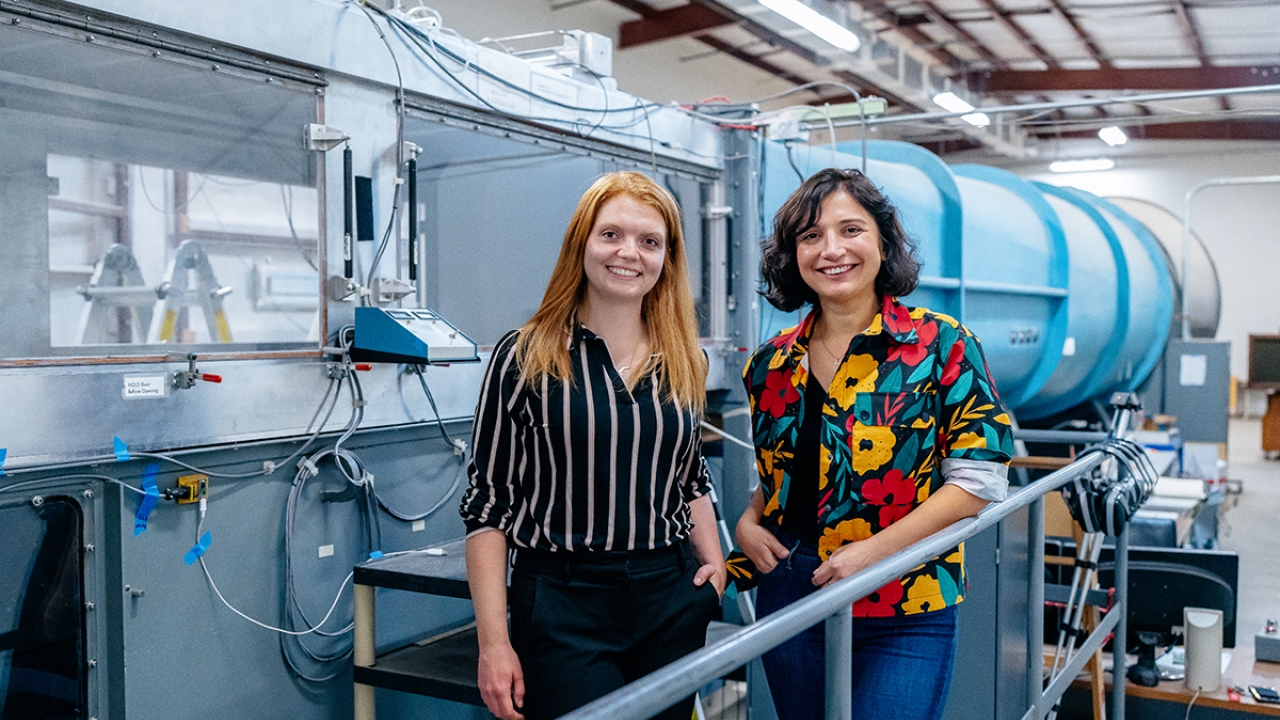

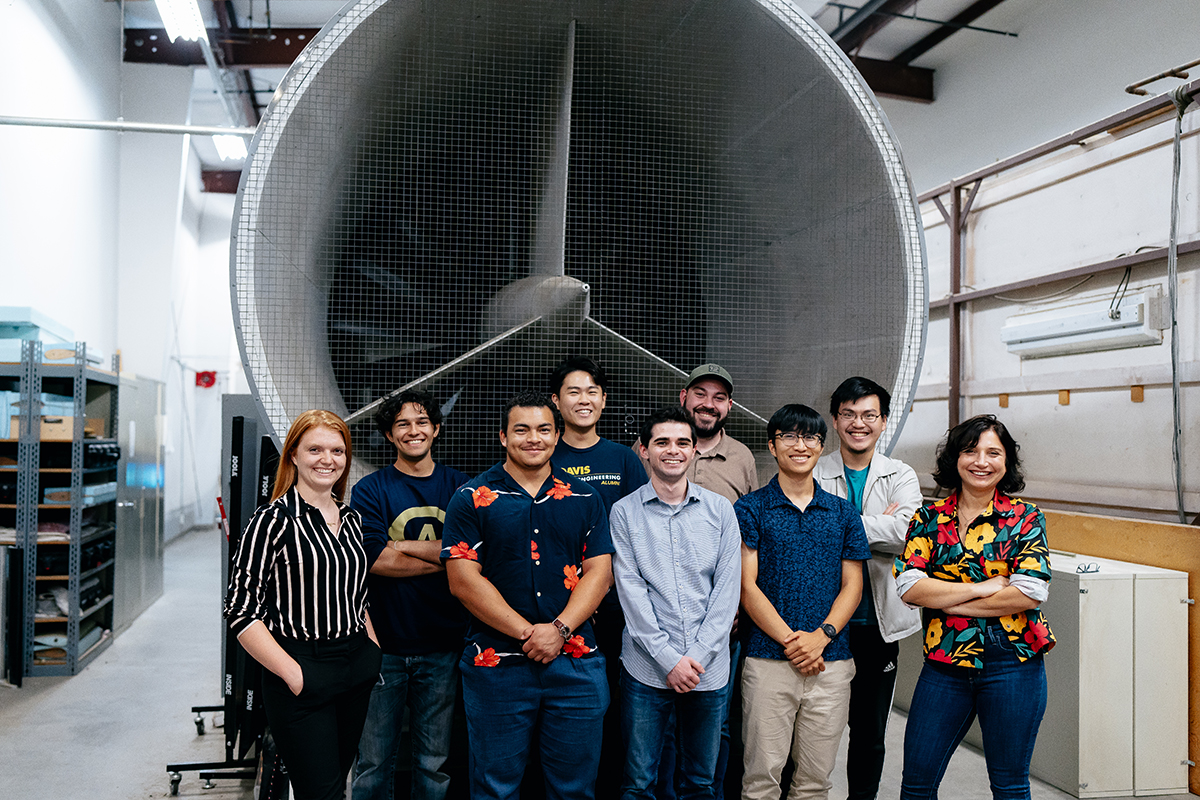

Now, a new class of aerospace faculty, namely assistant professors Camli Badrya and Christina Harvey, are on a mission to modernize the wind tunnels.

The two junior faculty members started at UC Davis last fall and are excited by the promise of using the wind tunnels for their research. They plan to integrate modern measurement technology, like infrared scanners that can measure the effect of the boundary layer on an aircraft wing, and particle image velocimetry, or PIV, that can map the velocity of airflow using neutrally buoyant particles.

Badrya, who is working on a novel class of airfoils, points out that with wind tunnel revitalization, UC Davis can be a leader in breakthrough aerodynamic research.

With its low-speed capacity, the AWT, in particular, is ideal for studying smaller aircraft and birds. For Harvey, who studies birds in flight to inform better aircraft mobility, the tunnel could facilitate advanced research into new methods of flight.

"These wind tunnels are crucial for the development of aircraft used in urban air mobility, rescue operations, and severe conditions such as wildfires that operate under dynamic conditions and often face unsteady air loads and flow separation," Badrya said. "By conducting experiments and publishing our findings, we can position UC Davis at the forefront of cutting-edge research in aviation."

Taking Flight with Wind Tunnel Research

Van Dam stresses the importance of having wind tunnel research facilities as a training ground for students, particularly in graduate programs. Students who run experiments on wind tunnels and build a fundamental understanding of how they work are often recruited to agencies like NASA because they have qualifying, hands-on experience.

Mechanical and aerospace engineering professor Steven Robinson, who strongly supports Badrya and Harvey in their wind tunnel efforts, stands as proof of this concept. He conducted wind tunnel experiments under Bruce White's supervision as an undergraduate student at UC Davis, which led to a 36-year career at NASA. While there, he was in charge of roughly 20 wind tunnels.

"One of them was a Mach 20 wind tunnel, one was about the size of a city block," said Robinson, who credits his university experience on wind tunnels as a key impetus for his career. "It really all started with the UC Davis wind tunnel."

"What we want to be doing is training the absolute top aerospace engineers," said Harvey. "I think it's really important that we provide our students the ability to be at the cutting edge. We have the capability to train at the top level."

To train at the top level, Badrya and Harvey agree that a university needs wind tunnels and wind tunnel experiments. While computational tools, some involving machine learning and AI, are becoming more widely relied upon in research, the numerical aspect of a theory is only half the story. This marrying of methods was a big reason Harvey and Badrya were so attractive to the department, said van Dam.

"You need the computations, and you need the experiments," said Badrya. "They complement each other, they do not replace each other. We want to make sure that our methods are valid in the physical world, and one way to do that is wind tunnel experiments."

Tunnel Vision

Five years from now, Badrya pictures a UC Davis with an entire complex devoted to wind tunnels with multiple facilities housing multiple different wind tunnels, from more advanced versions like the closed-circuit subsonic wind tunnel to the more basic like the Atmospheric Boundary Layer currently residing adjacent to Bainer Hall, but with state-of-the-art measurement systems.

"There is a lot of technology and a lot of science behind the wind tunnel and the measurement techniques," she said. "You get to do a lot of physics, you measure pressure, temperature, velocity. However, it's not limited to just fluid dynamics or mechanical systems; it also provides students with the opportunity to explore multidisciplinary engineering."

In Robinson's view, wind tunnel experiments are capable of opening students' eyes to not just wind tunnels, not just aeronautics, but the greater world of research.

"If the students do something with wind tunnels, they become well-versed in the entire process and challenge of experimental validation of numerical predictions," he said. "If students learn to do experimental research on a wind tunnel, they've learned to do experimental research period. It's like a portal into the future."

In Badrya's future, she sees UC Davis as the top research facility for experimental aerodynamics in California, collaborating with industry and research partners both nationally and internationally. Robinson is enthusiastic about the two professors.

"It's the ingredients for a wonderful recipe for a major research facility here at UC Davis," he said of "top-notch, world-class" professors Badrya and Harvey utilizing the modernized wind tunnels.

Harvey agrees, believing that the university has everything it needs to make that vision a reality.

"We have all the capabilities to be a leader in the field," she said. "We need to establish ourselves as a top aerospace program, and this is our time to make that stand and claim that space."